Growing up in Bellingham, WA meant that I’ve been surrounded by craft beer my entire life. I can remember my parents and their friends drinking at Boundary Bay, or bringing a six-pack of Full Sail over for a BBQ, but it wasn’t until years and years later that it fully clicked in my head that craft beer in Washington was something really special.

My dad came to visit me for the weekend when I lived in Seattle, and he claimed that he’d brought his favorite beer as a gift. He pulls the cans out of his cooler to transfer it into my fridge only to find out that I, completely independently and without talking it over ahead of time, had already stocked my fridge with the very same beer.

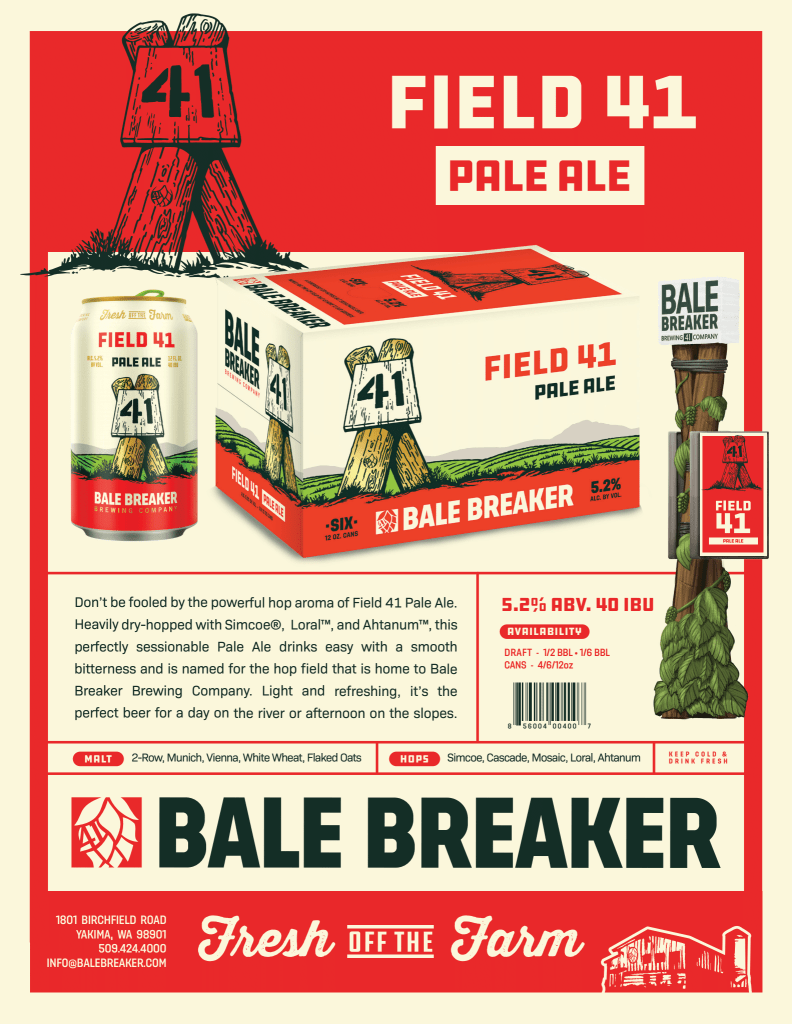

This was Bale Breaker’s Field 41 Pale Ale, and that night my Dad and I cracked open more than a few while expressing our love for the the crisp, hoppy flavor, and the homegrown approach Bale Breaker took in brewing beer from hops they themselves grew. I’d never really thought about the craft brewing process until that moment, and how proud I was to live in a region that had the capability to produce something so wonderful and unique, and do it almost entirely locally.

Now, almost a decade later, I’m following my dream of becoming a brewer, so I thought it would be a great opportunity for my practicum project to get more brewing experience by trying to brew my own version of Field 41. I’d learn while also developing a closer relationship with a beer that has a lot of sentimental value to me and my family.

Developing a recipe

I was originally planning on using sensory analysis to reverse engineer the recipe for Field 41, a task that would’ve been time consuming and far too extensive for the scope of a single, 10 week school quarter, so instead I decided to reach out to the source, Brian Logan, the Production and Quality Manager at Bale Breaker Brewing Company. One of the massive benefits of being a student in the brewing program at CWU is being able to have access to members of the craft brewing community, and pick their brains and dive into their expertise.

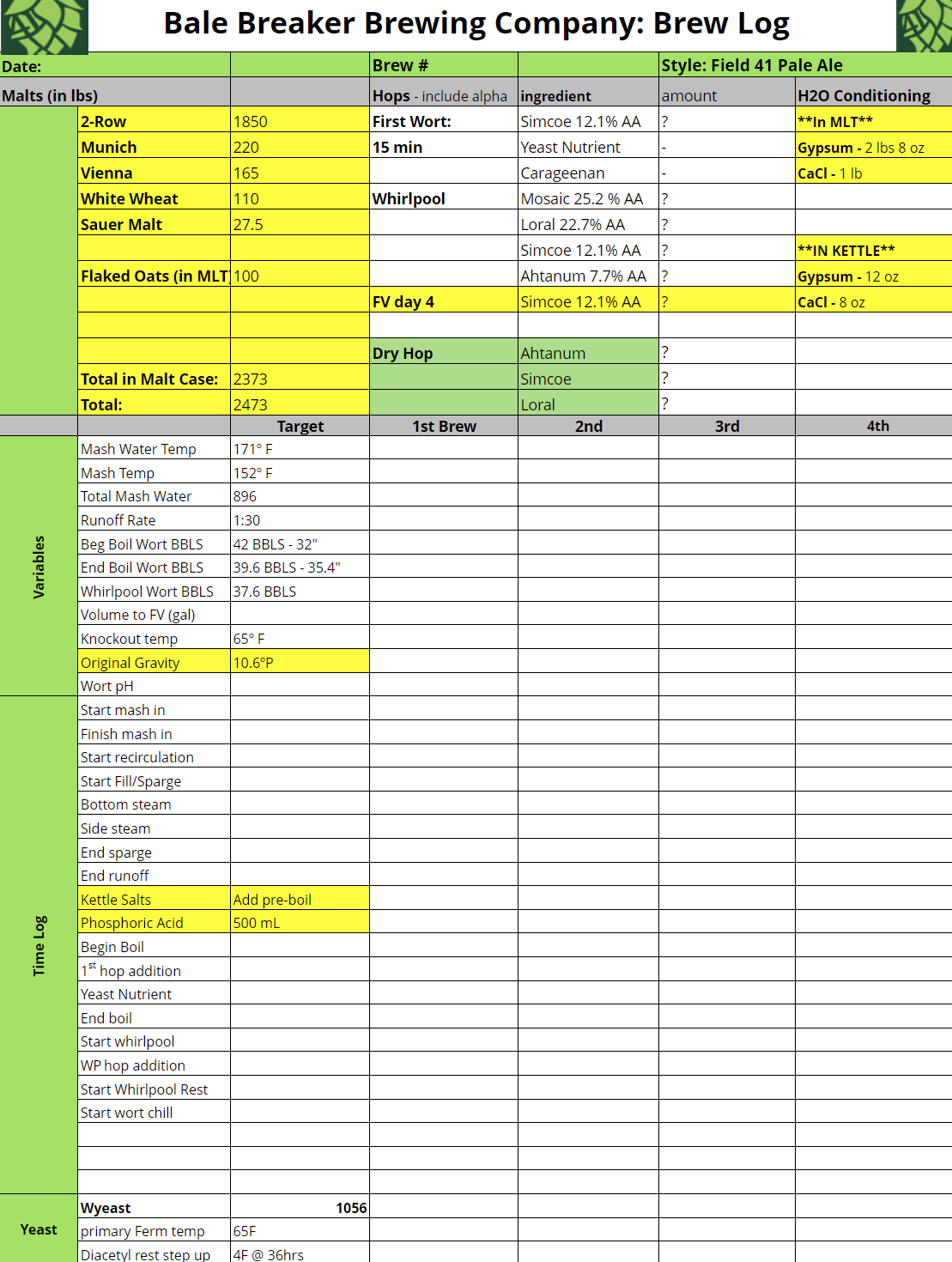

I’d done some digging and was able to find the bones of the Field 41 recipe, but just like when baking a cake, knowing the ingredients is only a small part of the battle. I still wasn’t sure about quantities, mashing profile, the use of protein rests, or quantities of hops and when they’re added, fermentation temperature, gravity targets, or dry hopping, just to name a few. This is where Brian Logan donated his valuable time and allowed me to see the recipe they use at Bale Breaker, a resource that I’m still thankful to have. Myself from 10 years ago is so jealous right now.

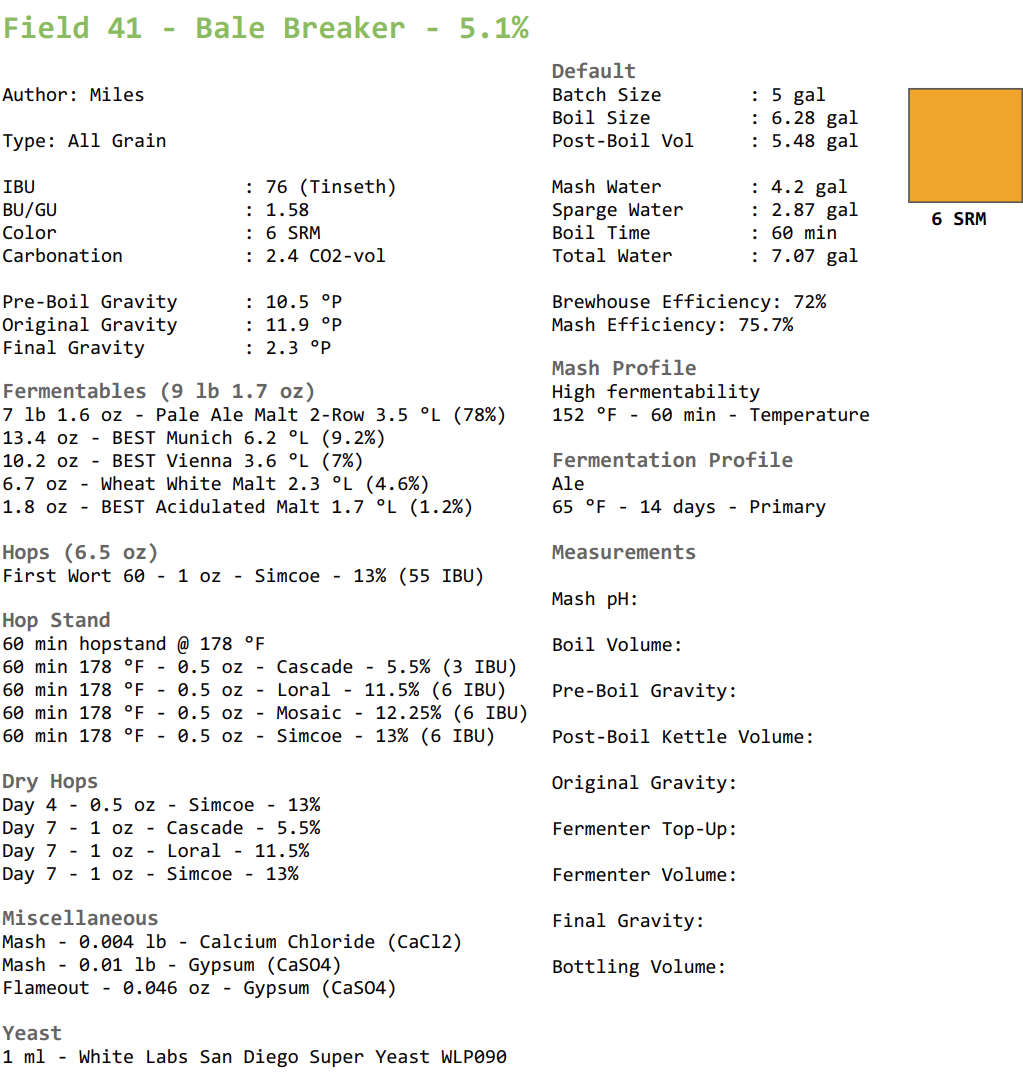

Translating a 42 barrel (1,302 gallon) recipe down to my 5 gallon homebrew setup might sound as simple as doing a little division, which is what I did, and I really don’t have any other option for my first brew attempt, but even if I nail every single detail on a smaller scale I should be prepared for the result to not match the big brother Field 41 version in flavor. Brewing chemistry differs when the volume changes by this much, in addition to the equipment I’m using being completely different as well.

One thing you might notice about this recipe is that the “amount” column for all the hop additions are left as question marks. While discussing the idea I had for my practicum with CWU Craft Brewing faculty member Cole Provence over a few pints he convinced me to leave a little mystery in the recipe so that I’d still have to use some sensory analysis skills to try to figure out the missing pieces. Brainstorming is best done over beer, but decisions should be made the next morning, and the next morning I still like the idea, so I asked Brian to remove this information from the spreadsheet, adding a little bit of an extra challenge. At the least I still had which hops would be used in the appropriate step of the brewing process.

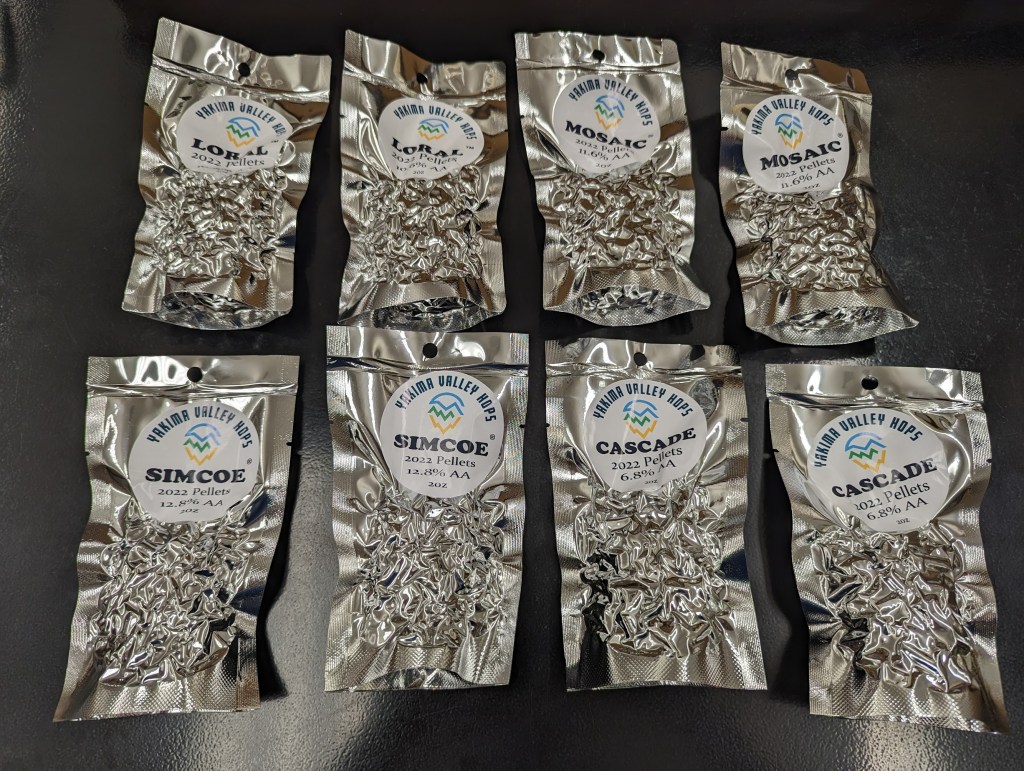

One thing I like to do whenever I’m brewing is to keep track of what I’m doing with as detailed notes as possible. I put together a recipe in BrewFather, an app that’s worked really well for me, just so I wouldn’t have to use my terrible memory to recall what I’d done. It also lets me keep track of any changes I make along the way, purposeful or not, for example I wasn’t able to get ahold of Ahtanum hops, so I swapped them for Cascade, which was a varietal used in Field 41 in the past.

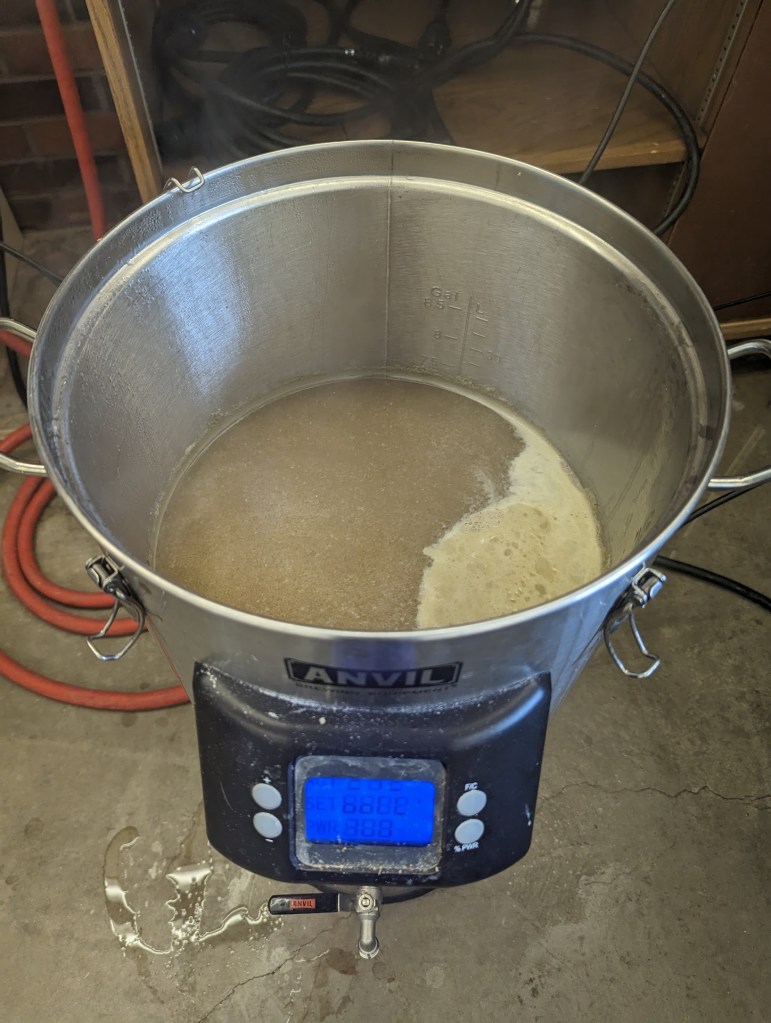

Brew Day

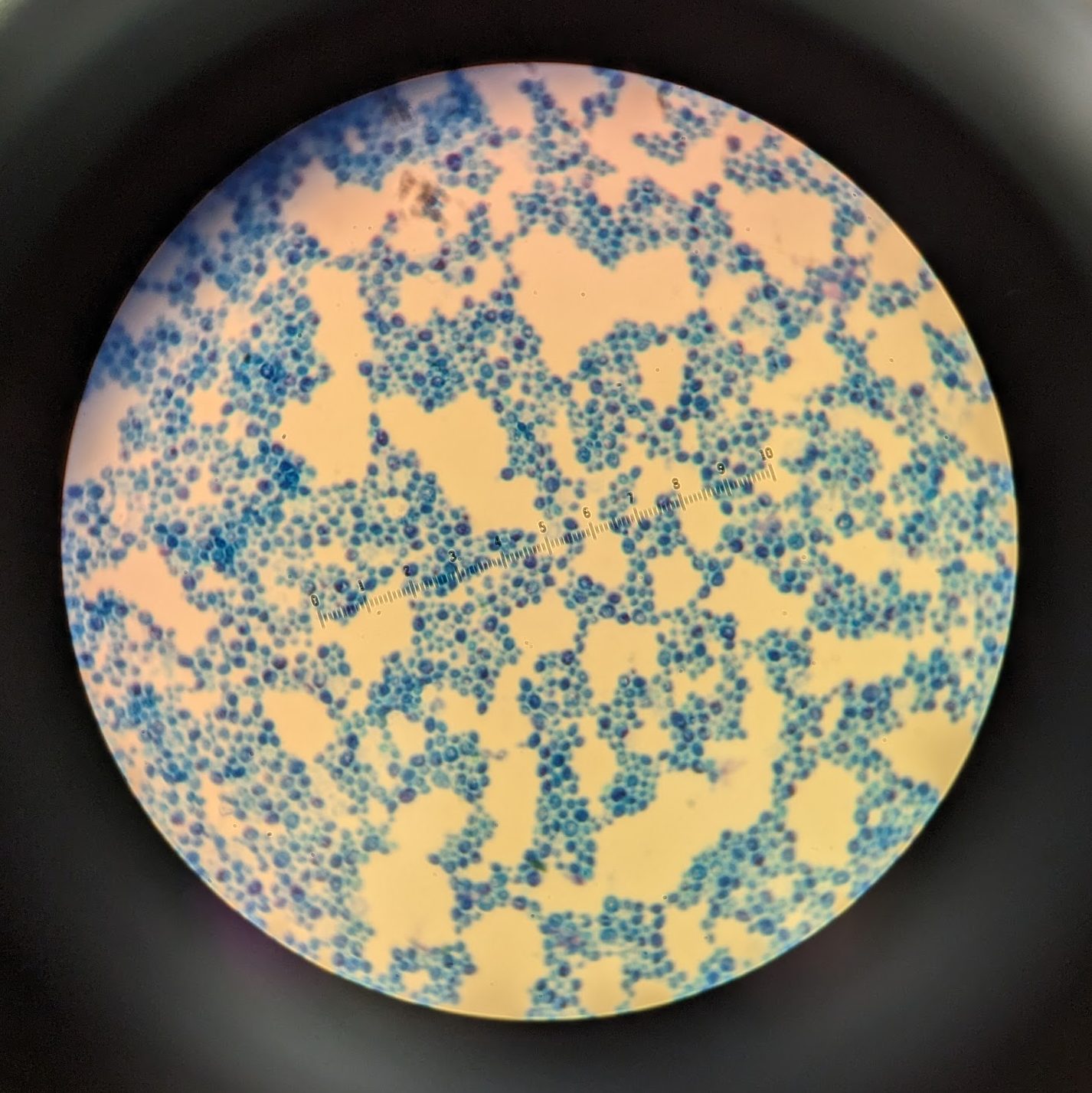

After making a trip to Yakima Valley Hops I was ready to start the brew. The CWU brew lab was already stocked with the malt I needed, and we had some ale yeast that we’d been propagating for our Microbiology of Brewing lab, San Diego Super. To ensure the proper pitch rate I took a diluted sample and did a cell count under the microscope, enabling the right amount of yeast to consume all the sugars in the wort at the proper rate without getting too stressed out. Brewing yeast is very particular about the environment their in, and I can’t blame them too much. They do great work when they’re happy.

Based on the gravity (10.3 plato times 1.0 x 106 cells/mL) multiplied by the the volume of the wort (19873 mL), and divided by the the viability of the yeast cells (8.2 x 108 cells/mL) I could calculate the volume of yeast I needed to pitch when it came time for fermentation, which was about 250 mL on the dot. This was my first time doing a yeast cell count, which I was really excited about because it’s just one more tool in my belt to have control over the brewing process.

The rest of the brew, from mashing to fermentation, was pretty standard for an ale. One interesting thing about this recipe was that non of the hops were added during the boil. There was an addition in the wort pre-boil, and a hopstand addition post-boil, but nothing during actual boiling point. This will probably help prevent isomerization with the alpha acids in the hops, limiting the amount of bitterness and focusing on the aromas instead, which is certainly evident any time you drink a Field 41 brewed by Bale Breaker.

This beer was also my first experience with dry hopping, which meant coming in a few times a week to add extra hops during fermentation. As of writing this the dry hop additions have been added, and the fermentation temperature has been raised a few degrees for a diacetyl rest. The gravity has dropped to a fairly dry 1.3 plato, but I’m planning on kegging on Friday, May 26 if all sticks to plan.

Next steps are to let this batch condition, and then do a taste test, comparing it to a can of Bale Breaker brewed Field 41 Pale Ale. I’m already planning on my next brew day of Tuesday, May 30, but the timeline means that this version won’t be ready to taste until the quarter is over, which I’m personally fine with since I plan on continuing to brew this recipe until I can get the kinks ironed out.

It’s been a really rewarding process working with Brian Logan at Bale Breaker, and the CWU instructors Brian LaBore, Cole Provence, and Eric Graham. Thank you all!

One response to “Brewing a Bale Breaker Field 41 Pale Ale Clone, Part 1.”

[…] post continues from part 1 found here: cwucraftbrewing.org. At the end of the last post I was talking about kegging if “all went well,” which it […]

LikeLike