Hi, I’m DJ and I’m a craft brewing major here at CWU. However, I am more interested in mead than I am beer (but more interested in beer than I am wine), so I decided to have my practicum centered around braggots, a beer-mead hybrid, and I looked specifically into the process of how they are made. Most (if not all) braggot recipes call for you to add your honey after you’ve boiled your standard beer wort, mostly because you lose out on many of the great natural properties of honey when you heat it up to a boil. I wanted to see just how significant of an effect it actually has on the final product.

To start, the main issues I found in the beginning of my project was determining how much supplies I need and what quantities I needed, the central supply being honey. Through Dr. Graham I was able to order a bucket of local wildflower honey from a friend of his in Yakima. The honey itself had quite a powerful flavor, which I was initially worried about but I figured that the full process of the brew would dim down the flavor.

To start, we wanted to make a large excess of the initial wort. Not only for me, but for another project as well. Having an excess of the wort allows us to have a uniform wort to split for the two styles; one to add our honey to for the boil and one to add after the boil.

First, we milled some 2 row pale malt (about 8 lbs).

Our goal for the mash was 152° f and a pH of about 5.3. The strike water we used had a pH of 8.32 and a temperature of 155° f. We started the mash at 9am and let it rest at 9:09 with a temp of about 152° f (our target), but with a pH of about 6.05, which was higher than we wanted but honestly 5.3 was just an estimate, plus we figured that we could lower the pH later in the process. The Gravity of the mash at this point was 1.016

We started the vorlauf at around 9:40, and just with that hour and ten minute long process, the pH lowered to 5.91. We did have some issues with the pump, sometimes the water pressure would be very low and the recirculated wort would only dribble out and other times it would come out fast enough that it would hit the other side of the kettle. The gravity at this point was 1.043

For sparging, we did lower the pH of the 165° f sparge water, but the pH was only 7.12. But after that, we moved on to the boil which is where the experiment began.

This consisted of splitting our current wort in half and adding honey to one of them. we used 2 pounds of honey in total, 1 pound for each gallon. Our initial calculations indicated that 1 pound of honey would raise the gravity of 1 gallon of wort by about 35 significant gravity points, but in practice, it was only raised the pre-boil wort by about 18, putting our pre-boil gravity at 1.054 for the braggot wort being boiled with honey (which I will now refer to as “honey boil”) and the braggot wort being boiled without honey (“non-honey boil) at 1.036. However, after the the boil, the honey boil was up to 1.068 and the non-honey boil was at 1.070, meaning that the total gravity point change was only off by 0.001 for the non-honey boil and 0.003 off for the honey boil. Another conversation we had was what to do for preventing the braggot from becoming syrupy. The initial thought was to add tannins but we found out far too late that the brew lab was out of tannins. I had done some side research into some older mead recipes, and I found one from the 80s that mentioned using tea for its tannic acid to offset the sweetness. I proposed the idea to use green tea in the boil, which had a pretty neutral flavor that wouldn’t take away from the flavor of the braggot itself. But in the end we decided to use hop pellets, specifically Idaho Gem. We didn’t use very much, only about 6 grams for each wort, but we figured that it would be enough to prevent over-sweetness while not taking center stage for the flavor profile. The final pH for the post boil worts was 5.28 for the honey boil and 5.30 for the non-honey boil.

After all that was said and done, we let it cool, moved it to our carboys to ferment, put a packet of American ale yeast in, and corked them with airlocks to let them ferment for 10 days. (We even had some of both worts left, so Brian had the idea to put them together with some English ale yeast just to see how it turns out!)

10 days later, we checked up on them to see just how done the fermentation was. We took a reading of the gravities, and the honey boil was down to 1.007 and the non-honey boil was down to 1.006. We racked them from the carboys to a small keg, and just to be certain that the fermentation was truly complete, we thought to monitor the pressure and check back in a couple days to not only check the pressure to see if it had increased, but to also check the gravity to see if it was lower. After a few days, we noticed that it had indeed been still fermenting in the keg, but only a little bit. Both gravities had lowered to 1.005 giving us an ABV of 8.27% for the honey boil and 8.53% for the non-honey boil.

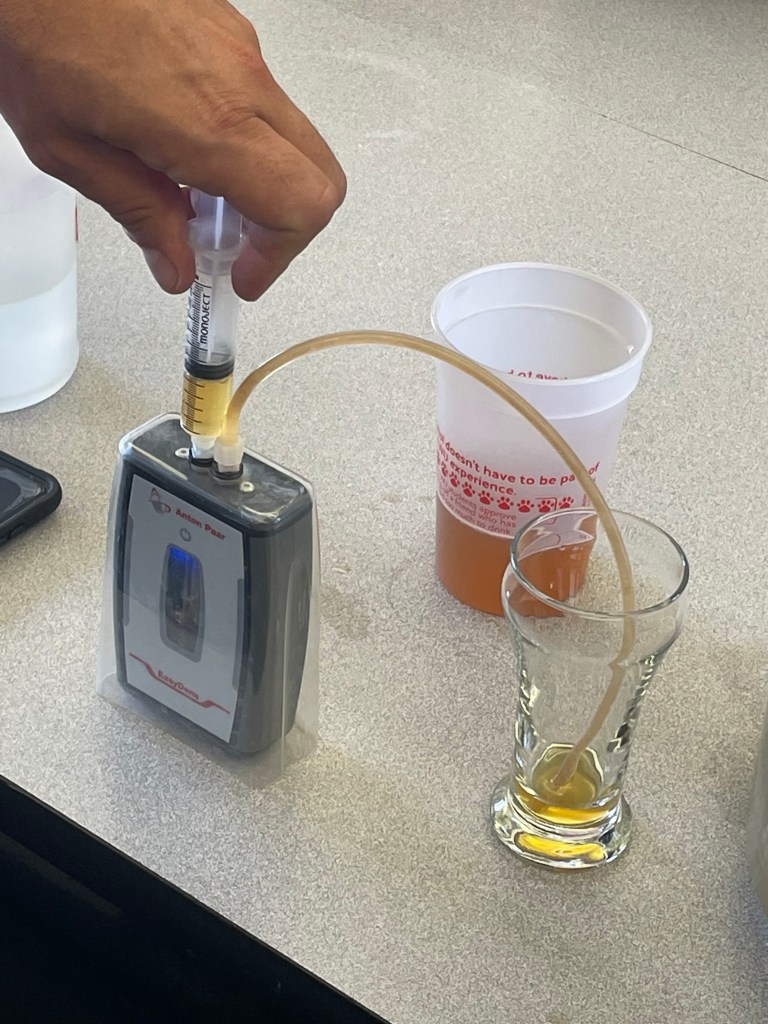

We weren’t done yet. After confirming that fermentation had stopped, we had to carbonate and chill the braggots. which would prepare them for the final test, a triangle test conducted with the Sensory Analysis for Brewing class to test if (with an admittedly small panel of judges) there was any significant difference between boiling your honey and not boiling your honey.

The Final Notes Writeup

A quick summary: My project was to determine the significance of a rule when using honey in brewing: never boil your honey. I’m more interested in making mead than beer, but I still wanted to try something new and relevant to what I am learning in the craft brewing department.

The initial proposal I had was clear, concise, and for the most part organized. But I learned more than what I sought out to. I learned how complex the logistical aspect of brewing can be, I learned about how important it is to stay on top of what you need and how much you need, I learned just how important it is to communicate with the people you’re working with, and I learned just how fun and rewarding the brewing can be if you have a wide resource of people willing to help you. Everything felt pretty last second (including this final report!) and if I was more on top of what I needed, then maybe it would have been less stressful. Somethings you can’t control, like how long it will take someone to pick up your supplies or how long it will take to deliver. But what I could have done differently is ask much earlier about the current honey supply, and (after finding out that we had no honey) order it much earlier to compensate. I should have been more on top of my recipe too, I’m sure I caused unnecessary anxiety with the people I was working with by not showing them that I mastered all the information about braggots, braggot recipes, and the process of actually making them.

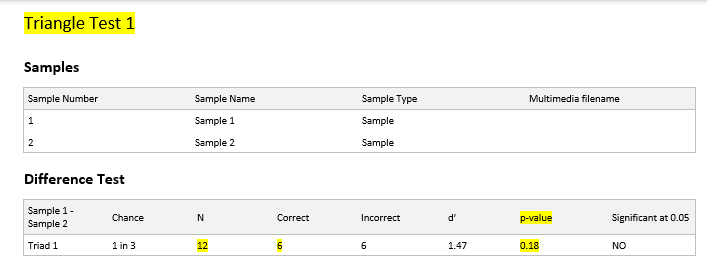

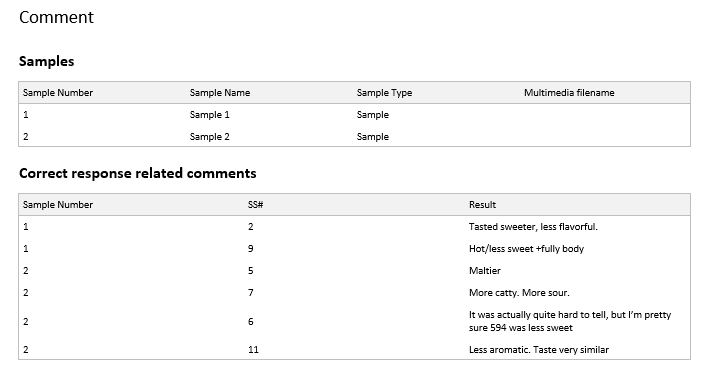

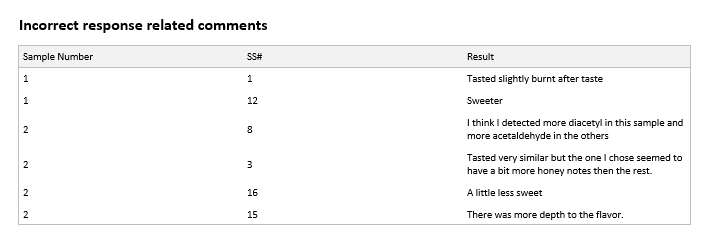

That aside, the last part of this project was working with the Sensory Analysis for Brewing class to use statistics to determine if there is a significant flavor difference in the final product. Ultimately, with 12 judges, we had a 50/50 split of correct and incorrect answers. With a p-value (statistical measurement used to validate a hypothesis against observed data) of 0.18, we can determine that there is actually no significant difference in the final product between adding honey during a boil and adding it afterwards. This null hypothesis would likely mean that any observed difference is due to sampling or experimental error. This data is of course to be taken with a grain of salt, because we likely had no where near the amount of judges we should have had, and this was done in such a small scale. In the future, should I do this again, it would be great to try this in a 5 gallon batch while also incorporating a wider pool of judges (potentially from multiple classes).

Judges were not able to distinguish these two beers from each other. However, with this small number of judges, I would recommend recruiting another 5-10 judges to clearly establish whether differences exist or not. With just 12 judges, just two more judges correctly identifying the odd sample would have established a difference existed.

Professor David Gee

I initially believed what all of the braggot recipes I saw were saying. But now I know that in the future I can be more lenient with when I put my honey in. I think that I will still opt to not boil my honey, but I definitely feel better about using older honey that may have started to crystallize because it can be boiled to achieve better clarity without losing much flavor in the final product.

I enjoyed this project! This fall I have an idea for another project that will be more focused on mead, and using different types of sugar with the honey.